Home

1981 Cooper Interview

Jackie's oral history interview with Terry L. Birdwhistell for the University of Kentucky Libraries’ John Sherman Cooper Oral History Project, 1040 Fifth Avenue, New York City, May 13, 1981

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I thought we'd begin by asking if you can recall some of your first impressions of John Sherman Cooper perhaps how you got to know Judge Cooper and his wife Lorraine.

Ms. ONASSIS: I think I first got to know him in 1952. I was married in '53. I remember that Jack and I used to go to Charley Bartlett’s for dinner — I was interested in Jack, and Senator Cooper and Lorraine were just going out together then. We had many pleasant evenings, and Senator Albert Gore was often there. So, I saw the Coopers a lot, and that's where we became friends. There were always just about six or eight of us. My first impression of Senator Cooper is the same as my present impression — his wisdom, his humor, such a fine, fine man. And over the years in the Senate — at least with Jack, who was running around the country so much campaigning — there are not that many senators who get to be your private friends as a couple.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right.

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, he was one of them, and he remained one. And afterwards, he was on the committee to figure out the kind of memorial we would make for Jack at Harvard, at the Institute of Politics. He gave so much time — he was always the wisest, I thought, of anybody at the meetings. He was a devoted friend.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Of course, in 1954, Senator Cooper was defeated by Alben W. Barkley. Then he went to be ambassador to India, and he came back to the Senate in 1956. Did you talk with them before they went to India?

Ms. ONASSIS: I suppose I did. You see, Ms. Cooper had been a friend of mine before. She used to ask me to dinner parties when I was still either in my last year in college in Washington or the year or so I worked on the newspaper.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Of course, the Coopers were married just before they went to India.

Ms. ONASSIS: What year did they get married?

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: In 1955.

Ms. ONASSIS: I know it was just about the same time that Jack and I married. We were courting at the same time, getting married at the same time.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: You were sharing a lot of the same experiences right there in Washington.

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Did you have much opportunity to talk with them or communicate with them while they were in India? No? A little far away for that, I suppose. How did you feel that they reacted to their experience in India? Had Ms. Cooper enjoyed being over there, and did you think that Judge Cooper enjoyed it?

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes, I do. I think that it was a very rewarding experience for them. I don’t really remember substantive things or problems, but I was very happy they could start out their married life where she could be very useful. She would be a wonderful ambassador’s wife! I was amused and charmed at the way she took to campaigning later, because she's such a — how can I say it? — sophisticated, elegant, decorative person. But, she has such a feeling for people. She was marvelous going all over Kentucky. I remember she told me that she carried little cards with her and that, whenever she left a town-she told me to do this campaigning, but I was too tired to ever do it! Right away she wrote a little note: “Dear So-and-so, Thank you for this.”

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right.

Ms. ONASSIS: Because, otherwise, everything piles up, and you don’t. And then she wrote a newsletter, I believe.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. That was very popular in Kentucky.

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: It appeared in all the little weekly surrounding…

Ms. ONASSIS: And I remember seeing some of those. I think she even told me I should do that, too — but I think I only did one!

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I was going to ask you about her campaigning. Did she ever express to you any negative thoughts about campaigning in Kentucky? Was it all more or less positive?

Ms. ONASSIS: I think she liked it. Some people are made for public life, and some aren’t. I think, as I’ve said, she loved people and seemed to respond to them. And it’s nice to feel that you can help your husband.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Yes. And, when they went to India, she spent a lot of time redecorating the embassy residence.

Ms. ONASSIS: I remember she told me that she organized the embassy wives for projects — I forget what — but she contributed a lot.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Now, later you went to India, I believe. Did anyone remember that…

Ms. ONASSIS: Oh, yes!

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: ... Judge Cooper had been there?

Ms. ONASSIS: Oh, yes, of course. John Kenneth Galbraith was ambassador when I was there. Obviously, nobody was going to make comparisons, but I'm sure he must have been as respected and loved. You were proud for America when Judge Cooper was wherever he would go. In my time it was always insulting when people would say to you, “Oh, one would never think you were an American.” But I think of Judge Cooper and David Bruce as Americans — the finest, and yet not getting so fancied up that you’d think they were foreigners. Of really being rather Jeffersonian, in a way.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: That's good. That's a good description.

Ms. ONASSIS: And, of course, David Bruce’s life wasn’t diplomatic posts. But I think Judge Cooper — he had two very important ones — wherever he would have gone, he would have been superb.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: He seemed to really like that aspect of his career — the State Department, the United Nations, the ambassadorships that he had to India and East Germany. What was it, in your opinion, that allowed him to be a country judge in Somerset, Kentucky, and be an ambassador around the world?

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, couldn’t you ask that same question about Abraham Lincoln? I think if you have deeply human qualities, you have great intelligence, wisdom, compassion. You see, some people can be very intelligent, but they can put the person they are talking to — they can get their back up, because they may make them feel inferior, or that they’re pressing him. So, even if he were speaking to someone whose views or ends were opposed to his, there must have been great human contact established. That’s where I think his great value was.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: A feeling of concern for whoever he was in…

Ms. ONASSIS: A sensitivity …

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: … sensitivity.

Ms. ONASSIS: … to the other person. And then you could tell from the way he was. It’s a question of character, really. If the man seems to you wise, profound, compassionate, intelligent, learned — well, you're going to look up to him. And then he was also loved. He couldn't help but be loved — if you just spend fifteen minutes with him, you're going to like him.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: It's interesting, the friendship that developed between the four of you when you were going out. And then, of course, Senator Cooper came back to the Senate in 1956 and was serving with your husband then. Although they were in different political parties, they worked on legislation such as aid to India and other types of bills, so, obviously, this personal friendship then carried over to a political friendship.

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes, but don't you think that a liberal Republican and a Democrat — you know, they felt the same about many things.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: So it really wouldn't have been that unusual even if they hadn't been such personal friends to have worked together on …

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, now, maybe it was an anomaly. I don’t really know. But I think that both of them were original enough, or not so narrowly partisan, that they could appreciate the qualities of the other. Well, you get a lot done in the Senate with bipartisan things.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right.

Ms. ONASSIS: Then, we'd see a lot of each other. We had a little house in Georgetown from, I guess, 1957 to 1960, and they’d come for dinner a lot.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I’ve been told that during the 1960 campaign, as you well know, the West Virginia primary was so crucial. Someone said that President Kennedy asked Senator Cooper for some advice on how to campaign in that state? Are you aware of that at all?

Ms. ONASSIS: I’m sure he did. It would have been very smart of him, and it doesn't surprise me. But I don’t remember what Judge Cooper said.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Of course, Senator Cooper was running for re-election in 1960, at the same time the presidential campaign was going on, and President Kennedy came to Kentucky and was campaigning. Did you all ever talk about that socially, or was that just sort of accepted in political life that …

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, you know, things speeded up so fast that year of 1960. Then I was having a baby, so I wasn't there. Well, probably we did. It’s really a shame when I sort of never wanted to — so many people, you know, hit the White House with their dictaphone running! I never even kept a journal. I thought, “I want to live my life, not record it.”

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Not record it every day?

Ms. ONASSIS: And I’m still glad I did that. But I think there’s so many things that I’ve forgotten. And I'm sure we did talk about everything you’re asking me about.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. Well, of all the things you said were going on in 1960, to pull conversations at a dinner table, when you're trying to relax to begin with …

Ms. ONASSIS: No, no, no. We would have talked about it, of course —everything! Of course, the conversation was political! Of course, it would be —with Jack and Judge Cooper and Lorraine and me — but I don't remember specifically any sentence.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right.

Ms. ONASSIS: To show you what good friends we were — I think I'm right in this — the first dinner party we went to after we were in the White House was at the Coopers'.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. And that interested a lot of people that the first dinner party would be at the home of a Republican!

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, they were just our beloved friends. We'd made the date before. I think it was for some dance or something in Washington that was sort of an occasion. We didn't go to the dance, but went to the Coopers’ for dinner.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I think there was a snow storm that night, wasn't there?

Ms. ONASSIS: Oh, yes. I guess the Secret Service ran by with so many loads of sand and everything. You know, it was meant to be rather quiet, but the press was outside. I remember thinking, “Well, I'm happy if they're surprised, because if it shows paying homage to Senator Cooper — good. Who's there more worthy of paying homage to?” But it was just a natural thing.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I think, also, that following the election before the inauguration — Life magazine did a “day-in-the-life-of” feature, and you had them over for that, didn't you?

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, they were coming for dinner. You know, Life hangs around, and I must say the two people who were doing it were Don Wilson, who lived in Washington, who was a friend of ours, and then Mark Shaw, the photographer they assigned to it, sort of became a friend. So, what they do is hang around and photograph whatever is happening. And so, maybe I asked the Coopers — I can't remember if they were coming for dinner anyway, and I said, “Oh, God, Life magazine's doing it, so I have to have … would you come?” But I remember they came to the first dinner party I ever had when we were married. The first year we were married we lived in a rented house, and it was just rented from January to June because in those days the Senate was in session then. I remember the Coopers came, my mother and stepfather came, and I’m sure Bobby and Ethel came. I don't know, maybe there were ten or twelve people. And I had some records on the record player, and I think my mother was quite nervous about —you know, I'm not sure I had it all together then. Suddenly, she said, “Jackie, isn't the record player broken?” And I said; “Oh, no, Mommy, it's just Fred Astaire tap dancing.” Lorraine thought that was very funny. She used to remind me of it from time to time. So, you see, for so many sorts of firsts, they were just … Maybe we had four couples who were really close friends before the White House. After the White House, another one would have been the Harlechs, from England, who came as British ambassador. But before, the Bartletts — well, anyway, the Coopers, you know, they were just our really close friends.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Yes. And I think it shows that you remember the first time you did this or that, and those are the people that you would want there. I've talked to other people who lived in or worked in Washington, and sometimes people don't develop that type of friendship.

Ms. ONASSIS: You always hear about Washington — all this going out and party circuit. We never did that; we didn't like it. Then Jack would be traveling a lot, so we just liked to stay home. And there were a couple of houses that you'd go to for dinner or else you'd have your close friends over rather informally. It was fun to go to the Coopers. It was fun to go to Joe Alsop's, the columnist, because he'd always have rather stimulating dinners, and if some foreign political figure or whatever was coming, that was always rather stimulating. You work hard all day, and then you like to be with a few — at least that was the way Jack operated, and it's the way I like to live, too.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Senator Cooper recalled a story. He was talking about soon after you all moved into the White House, that there were some films being shown at the Indian Embassy, and President Kennedy didn't want to go by himself. Do you remember that night?

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes, I do. That was very shortly after the inauguration. Again, it was a date we'd made before, I think. I know that I had lived in Washington during the Eisenhower years, I'd lived there since I was thirteen, except for going away to school. I wanted to do something for the arts. So there was this film, by this wonderful Indian film maker, and Jack said he would go. Well, then I was really terribly tired when I got into the White House. I couldn't get out of bed for about two weeks! After the birth of my son, and the campaign — I mean you don't do anything. You know, you just sort of collapse.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Well, I think you deserved a little rest, probably.

Ms. ONASSIS: He was born prematurely, because of all the excitement. He was sick. I was sick. One just wasn't able — and yet, the Indian ambassador, all of that, it was set to go! So, anyway, Jack went with the Coopers.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Senator Cooper recalled that after they came back that President Kennedy insisted on giving them a tour of the White House, and he remembers they even woke you up!

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes, and that was in the beginning! That shows how early it was, because they were painting the quarters that we lived in, and we were in the far end where you live in the Lincoln Room and the Queen's Room. It's sort of like a big, vast, drafty hotel. It didn't seem very cozy! And I remember he brought them up, and I was so happy. You know, so that you could sort of share the evening and the laughs at the end and whatever.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: And, I guess, it again points to President Kennedy's and Judge Cooper's friendship. Senator Cooper recalled when President Kennedy was showing him around so enthusiastically, about all of these quarters and rooms, and this big new house that you were in. I suppose by necessity, though, that your contacts with the Coopers probably lessened a little bit during the White House years. It was probably more formal.

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, did they? I don't know. Of course, you had many more obligations in the evening, and many more evenings when you had to do something. There weren't those Georgetown evenings where you could just have your best, your dear friends, your old pals over. But it seems to me that we saw each other. I'm sure they came, you know, sort of in and out.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: When President Kennedy took office and his legislative program came up, of course Senator Cooper was supportive. One area, though, where he was openly critical — and it made the newspapers, I suppose — was in the Kennedy civil rights program. Cooper apparently thought it was going too slowly. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Ms. ONASSIS: I don't remember any talk about that. He thought it was going too slowly? Isn't that marvelous –— for a Southerner? You know, you would have thought he might have to say the opposite.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: That's one of the interesting things about his career. I was reading a campaign speech he made in 1948, when he opens his campaign in Kentucky, and he was advocating civil rights in Kentucky. And you don't see that too much from a Kentucky politician in the 1940s.

Ms. ONASSIS: He would have been such a wonderful Secretary of State – wouldn’t that have been wonderful? You can have so many brilliant people, but where can you get that wisdom, and that common sense?

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Apparently, before the inauguration, President Kennedy did send Judge Cooper to Russia on a mission. Do you recall that at all?

Ms. ONASSIS: Now, it rings a bell.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: It wasn’t public at the time, I don't believe, and he came back and gave a report to President Kennedy about the situation there.

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, that shows how much Jack would have valued his judgment — did value his judgment.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. So you would say, then, that you felt the Coopers enjoyed the social life, the political life in Washington? I know Ms. Cooper is a very well-known hostess in the city there.

Ms. ONASSIS: You know, I never like to say “enjoy the social life,” because I think that sounds trivial and frivolous. If this is being done for history, as if the social life is an important … I don't know, everybody rushes in. Who's in? Who's out? Dinner parties. You know, he's too profound for that silly treadmill I have no esteem for. But, yes, they loved people, and, after all, all the people you saw in Washington that you saw in their house, whose houses they went to, are involved in shaping policy. All the big receptions, the cocktail parties — forget that. I think I may have been to one in my life — or the big embassy dinners, even. I'm not sure that anything of substance is really accomplished there. But, there are very few people civilized enough — or were — to give a “twelve this and that” kind of dinner. And then it's awfully valuable, because the men can talk to each other afterwards. In those days, it used to be quite segregated! The men would absolutely split!

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: No pretense!

Ms. ONASSIS: The French know this — anybody knows this — if you put busy men in an attractive atmosphere where the surroundings are comfortable, the food is good, you relax, you unwind, there's some stimulating conversation. You know, sometimes quite a lot can happen. Contacts can be made, you might discuss something, or…

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: An understanding…

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes. Or, you know, you could be talking about a whole lot of things. You might have different foreigners there and then say, “Gosh, that's an idea. Maybe we ought to see each other next week on that,” or whatever. So it can be valuable that way. I always felt that going to the Coopers’ house … it was joyful, but it was never frivolous.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: I see.

Ms. ONASSIS: So, social life, where it's used, is part of the art of living in Washington.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Another person who mentioned going to a dinner party at the Coopers’ noted that the most fascinating thing was the people who were there, and the selection, and the talk that transpired. Now, others have said that Judge Cooper was always late for his own parties.

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, if he was, Ms. Cooper was such a marvelous hostess that you never really noticed.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: He was able to ease right on in there…

Ms. ONASSIS: And why shouldn't he be? Practically every senator — they're always up there for a vote. Sometimes half the dinner table doesn't get there until dessert!

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. Because of your close personal friendship, what was your reaction, then, to Judge Cooper’s being named to the Warren Commission? Any reaction at all to that?

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, I suppose I … well, I mean, obviously his wisdom … But, to tell you truth, everything that happened that caused the Warren Commission to exist —you know, I don't think I really sat and thought, “Hmm. Let me look at the make-up of the Warren Commission. Let this, that, you know.”

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right.

Ms. ONASSIS: Somehow I had this feeling of, what did it matter what they found out? They could never bring back the person who was gone. Obviously, I knew it had to be done. But, of course, I would have thought that his being on it was — any commission he's on will be better for having him on it.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Right. Well, then, as you said earlier about his work on the memorial, and the committees he served on, the people that talk about his work on the Warren Commission talk about how much effort he did put into it, you know, working many, many longer hours, to go to the meetings and do the reports — and just the manner in which he approached it, I suppose.

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes, that’s exactly what I noticed about Senator Cooper at these meetings that we would have in Boston. There’d be maybe two or three a year. You know, Robert McNamara was on it, Robert Lovett, Douglas Dillon, Lord Harlech — all these wise, wise people would come. And before, there’d be briefing books that big or, you know, material you'd have to digest, and it was very hard to see which way the Institute of Politics … what it was going to be like. Would it be swallowed up by Harvard? What should it do? And always, I'd notice I'd be so amazed at his absolute, thorough knowledge of the five pounds of paper that he had in front of him, and everything you say. And the real heart he put into it, and how — oh, Senator Jackson was on it — and how often when there was a point that was being hotly argued, or a bind you couldn't see your way out of, how often his voice was listened to, and usually was the path that turned out to be obviously the right one.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Have you maintained contact with the Coopers over the years?

Ms. ONASSIS: Yes. When did I last see him? I saw him this winter some place.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Oh, did you?

Ms. ONASSIS: Sometimes I've seen Ms. Cooper when she comes to New York. Whenever I see him I am just so happy.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Well, that's all the questions I have prepared. I appreciate your taking the time to do this today, and to talk about Judge Cooper and your friendship with him.

Ms. ONASSIS: Well, I envy the person who writes a thesis on Judge Cooper, because I can't think of anything more rewarding than studying him.

Mr. BIRDWHISTELL: Well, thank you again.

Sources: The Courier-Journal/Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries

Biography

Jackie's Biography (Official Congressional Record - 103 U.S. Congress)

Jackie's Biography (Official Congressional Record - 103 U.S. Congress)

Jacqueline Lee Bouvier was born July 28, 1929, to Janet and John Bouvier III in Southampton, Long Island, New York. She en- joyed the country life with her parents and her younger sister Lee. In what became life-long interests, she developed an expertise at horseback riding, an enduring love of books, and a great delight in writing poetry. Throughout her life, she chronicled special family events by combining her creative talents in a unique, and often whimsical way, to produce illustrated journals, poetry, scrapbooks, and paintings.

After her parents divorced and her mother remarried Hugh D. Auchincloss, the family expanded to include his children and a new baby half-sister and brother, Janet and Jamie Auchincloss.

Jacqueline attended Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut where she excelled academically. She was accepted at Vassar and attended for one year. She then studied in Paris, becoming fluent in French, before transferring to George Washington University in Washington, DC where she earned a degree in French literature in 1951.

Following her graduation, Jacqueline took a job as the ‘‘Inquiring Camera Girl’’ for the Washington Times-Herald, and formally met then-Congressman, soon-to-be-Senator, John F. Kennedy, at a dinner party. ‘‘I leaned across the asparagus and asked her for a date’’ he quipped. They were married on September 12, 1953. Their early years together were marked by the great sadness of a stillborn daughter, and life threatening back surgery for Senator Kennedy. But in 1957, their adored daughter Caroline was born. ‘‘I used to sit and wonder how it could be possible to be any happier,’’ Jackie said. In November of 1960, after the successful campaign for the Presidency, their happiness doubled with the birth of John F. Kennedy, Jr.

Jacqueline Kennedy became, at 31, the century’s youngest First Lady and from the moment of her magnificent debut at the Inauguration, captivated the Nation and the world. She began a com- plete restoration of the White House and encouraged Americans to take special pride in their Nation’s heritage and the effort to preserve it. Her televised tour of the restored mansion was watched by 50 million viewers, and the resulting increase in tourists who bought her newly created ‘‘White House Guide Book’’ has continued to fund White House preservation and acquisitions to this day. She established the first office of White House Curator, and is credited with saving the historic townhouses and heritage of Lafayette Square.

She promoted an awareness and appreciation of culture and the arts by showcasing the finest in those professions at special White House events. Intellect was honored with a dazzling din- ner for all the Nobel Prize winners. The state occasions she hosted with President Kennedy continue to be remembered for their sparkling originality, exquisite taste, and classic elegance. She intuitively understood that the White House belonged to all the people, and she wanted it to be an expression of pride in American achievement. She said simply, ‘‘I just think that everything in the White House should reflect the best of America.’’

President Kennedy summed up her impact abroad when he intro- duced himself as ‘‘the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.’’ Her natural style, gracious personality, and ability to speak numerous languages, created an outpouring of affection. At home, during a time of civil rights tension, she quietly made her position clear by integrating Caroline’s White House preschool group.

In August of 1963, she and the President shared the great sorrow of the tragic loss of their prematurely born son, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, who died a few days after his birth. But the Na- tion, and the world, truly came to understand and appreciate her valiant strength in November of 1963. During the agonizing four days of her husband’s assassination and funeral, her majestic example of remarkable courage and fortitude has never been forgotten. At a time of unbearable grief, she held the country together.

In 1964, she reestablished her life in New York City and devoted herself to her children. She campaigned for Robert F. Kennedy during his bid for the Presidency and his tragic loss brought additional grief to her family.

In October of 1968, she married Aristotle Onassis, and she and the children divided their time between Greece and New York. She became a widow again, when he died in 1975.

Concentrating on her love of books, she went to work and became a respected professional in the field of publishing, as an editor at Viking and Doubleday. She continued her efforts on behalf of historic preservation and was especially proud to have helped to prevent the destruction of New York’s Grand Central Station. In 1980 she helped Senator Edward Kennedy in his campaign for President, and the John F. Kennedy Library continued to benefit from her ongoing devotion and involvement in its programs and such events as the Profile In Courage Award.

Jacqueline found tranquillity and joy in the companionship of her close friend, Maurice Templesman. But of all her accomplishments, she was most proud of having been a good mother to Caroline and John, often in the most difficult of circumstances. ‘‘It’s the best thing I’ve ever done,’’ she said. She exulted in their successes and became a doting grandmother to her three grandchildren.

In her final year, she set an example yet again of uncommon courage and spirited grace, as she battled illness. In her final days she was, as she had become to the Nation throughout her life, an inspiration.

Source: gpo.gov

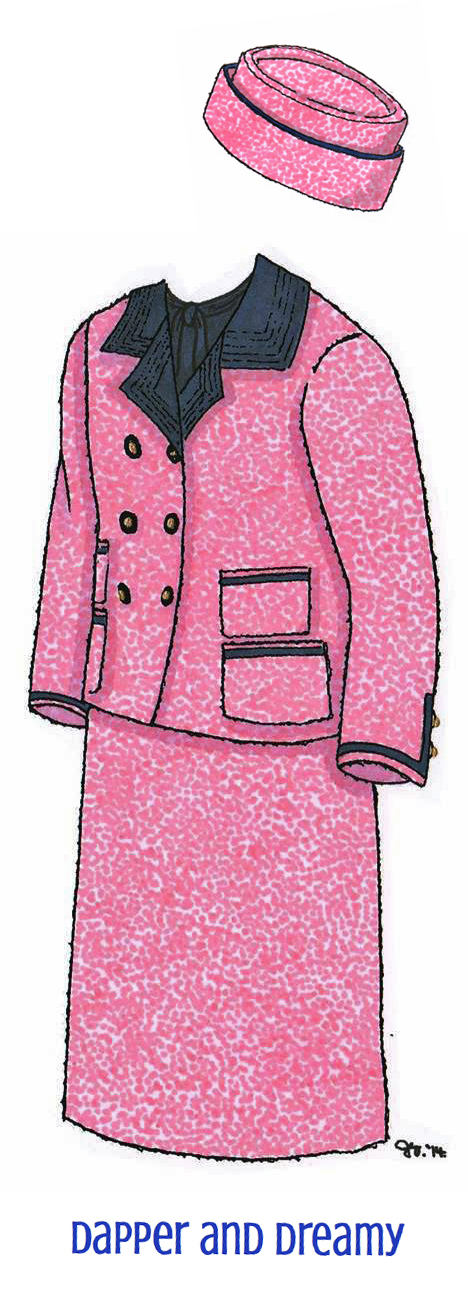

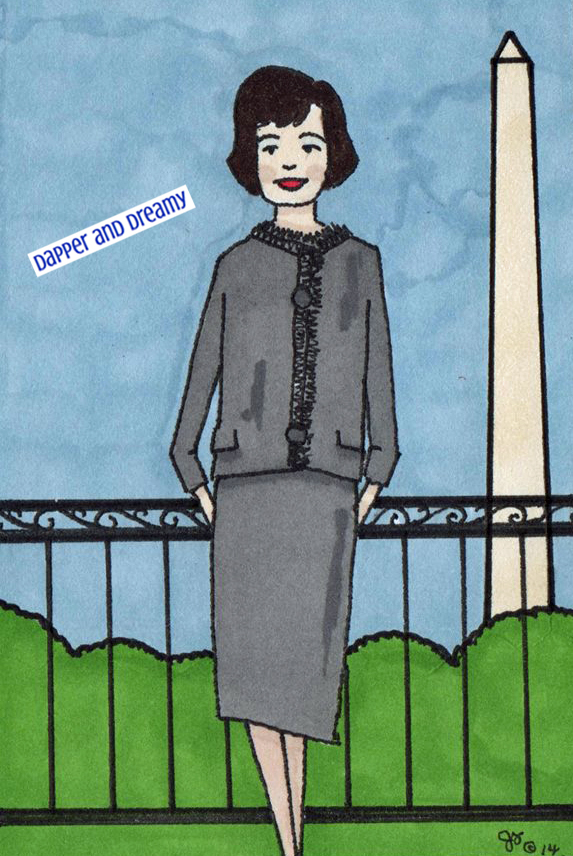

Image copyright Jake Gariepy (Dapper and Dreamy) - Jackie's 1961 Chez Ninon designed grey wool suit.

Galella Suit

Ron Galella v. Jackie

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

487 F.2d 986

Argued April 10, 1973

Decided September 13, 1973

Before SMITH, HAYS and TIMBERs, Circuit Judges [991].

J. JOSEPH SMITH, Circuit Judge:

Donald Galella, a free-lance photographer, appeals from a summary judgment dismissing his complaint against three Secret Service agents for false arrest, malicious prosecution and interference with trade (S.D.N.Y., Edward C. McLean, Judge), [note 1] the dismissal after trial of his identical complaint against Jacqueline Onassis and the grant of injunctive relief to defendant Onassis on her counterclaim and to the intervenor, the United States, on its intervening complaint and a third judgment retaxing transcript costs to plaintiff (S.D.N.Y., Irving Ben Cooper, Judge), 353 F. Supp. 196 (1972). In addition to numerous alleged procedural errors, Galella raises the First Amendment as an absolute shield against liability to any sanctions. The judgments dismissing the complaints are affirmed; the grant of injunctive relief is affirmed as herein modified. Taxation of costs against the plaintiff is affirmed in part, reversed in part.

Galella is a free-lance photographer specializing in the making and sale of photographs of well-known persons. Defendant Onassis is the widow of the late President, John F. Kennedy, mother of the two Kennedy children, John and Caroline, and is the wife of Aristotle Onassis, widely known shipping figure and reputed multimillionaire. John Walsh, James Kalafatis and John Connelly are U.S. Secret Service agents assigned to the duty of protecting the Kennedy children under 18 U.S.C. § 3056, which provides for protection of the children of deceased presidents up to the age of 16.

Galella fancies himself as a "paparazzo" (literally a kind of annoying insect, perhaps roughly equivalent to the English [992] "gadfly.") Paparazzi make themselves as visible to the public and obnoxious to their photographic subjects as possible to aid in the advertisement and wide sale of their works. [note 2]

Some examples of Galella's conduct brought out at trial are illustrative. Galella took pictures of John Kennedy riding his bicycle in Central Park across the way from his home. He jumped out into the boy's path, causing the agents concern for John's safety. The agents' reaction and interrogation of Galella led to Galella's arrest and his action against the agents; Galella on other occasions interrupted Caroline at tennis, and invaded the children's private schools. At one time he came uncomfortably close in a power boat to Mrs. Onassis swimming. He often jumped and postured around while taking pictures of her party, notably at a theater opening but also on numerous other occasions. He followed a practice of bribing apartment house, restaurant and nightclub doormen as well as romancing a family servant to keep him advised of the movements of the family.

After detention and arrest following complaint by the Secret Service agents protecting Mrs. Onassis' son and his acquittal in the state court, Galella filed suit in state court against the agents and Mrs. Onassis. Galella claimed that under orders from Mrs. Onassis, the three agents had falsely arrested and maliciously prosecuted him, and that this incident in addition to several others described in the complaint constituted an unlawful interference with his trade.

Mrs. Onassis answered denying any role in the arrest or any part in the claimed interference with his attempts to photograph her, and counterclaimed for damages [note 3] and injunctive relief, charging that Galella had invaded her privacy, assaulted and battered her, intentionally inflicted emotional distress and engaged in a campaign of harassment.

The action was removed under 28 U.S.C. § 1442(a) to the United States District Court. On a motion for summary judgment, Galella's claim against the Secret Service agents was dismissed, the court finding that the agents were acting within the scope of their authority and thus were immune from prosecution. At the same time, the government intervened requesting injunctive relief from the activities of Galella which obstructed the Secret Service's ability to protect Mrs. Onassis' children. [note 4] Galella's motion to remand the case to state court, just prior to trial, was denied.

Certain incidents of photographic coverage by Galella, subsequent to an agreement among the parties for Galella not to so engage, resulted in the issuance of a temporary restraining order to prevent further harassment of Mrs. Onassis and the children. Galella was enjoined from "harassing, alarming, startling, tormenting, touching the person of the defendant . . . or her children . . . and from blocking their movements in the public places and thoroughfares, invading their immediate zone of privacy by means of physical movements, gestures or with photographic equipment and from performing any act reasonably calculated to place the lives and safety of the defendant . . . and her children in jeopardy." Within two months, Galella was charged with violation of the temporary restraining order; a new order was signed which required that the photographer keep 100 yards from the Onassis apartment and 50 yards from the person of the defendant and her children. Surveillance was also prohibited.

Upon notice of consolidation of the preliminary injunction hearing and trial [993] for permanent injunction, plaintiff moved for a jury trial--nine months after answer was served, and to remand to state court. The first motion was denied as untimely, the second on grounds of judicial economy. Just prior to trial Galella deposed Mrs. Onassis. Under protective order of the court, the defendant was allowed to testify at the office of the U.S. Attorney and outside the presence of Galella.

After a six-week trial the court dismissed Galella's claim and granted relief to both the defendant and the intervenor. Galella was enjoined from (1) keeping the defendant and her children under surveillance or following any of them; (2) approaching within 100 yards of the home of defendant or her children, or within 100 yards of either child's school or within 75 yards of either child or 50 yards of defendant; (3) using the name, portrait or picture of defendant or her children for advertising; (4) attempting to communicate with defendant or her children except through her attorney.

We conclude that grant of summary judgment and dismissal of Galella's claim against the Secret Service agents was proper. Federal agents when charged with duties which require the exercise of discretion are immune from liability for actions within the scope of their authority. Ordinarily enforcement agents charged with the duty of arrest are not so immune. Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Fed. Bur. of Narc., 456 F.2d 1339 (2d Cir. 1972). The protective duties assigned the agents under this statute, however, require the instant exercise of judgment which should be protected. The agents saw Galella jump into the path of John Kennedy who was forced to swerve his bike dangerously as he left Central Park and was about to enter Fifth Avenue, whereupon the agents gave chase to the photographer. Galella indicated that he was a press photographer listed with the New York City Police; he and the agents went to the police station to check on the story, where one of the agents made the complaint on which the state court charges were based. Certainly it was reasonable that the agents "check out" an individual who has endangered their charge, [note 5] and seek prosecution for apparent violation of state law which interferes with them in the discharge of their duties.

If an officer is acting within his role as a government officer his conduct is at least within the outer perimeter of his authority. Bivens, supra, 456 F.2d at 1345. [note 6] The Secret Service agents were charged under 18 U.S.C. § 3056 with "guarding against and preventing any activity by any individual which could create a risk to the safety and well being of the . . . children or result in their physical injury." It was undisputed that the agents were on duty at the time, and there was evidence that they believed John Kennedy to be endangered by Galella's actions. Unquestionably the agents were acting within the scope of their authority. [note 7]

To be sure, even where acting within their authority, not all federal agents are immune from liability. Immunity is accorded officials whose decisions [994] involve an element of discretion so that the decisions may be made without fear or threat of vexatious or fictitious suits and alleged personal liability. Ove Gustavsson Contracting Co. v. Floete, 299 F.2d 655, 659 (2d Cir. 1962), cert. denied, 374 U.S. 827, 10 L. Ed. 2d 1050, 83 S. Ct. 1862 (1963). The issue in each case is whether the public interest in a particular official's unfettered judgments outweighs the private rights that may be violated. [note 8] See Bivens, supra, 456 F.2d at 1346. The protective duties of the agents on assignments similar to this warrant this protection. [note 9] See Scherer v. Brennan, 379 F.2d 609 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 1021, 19 L. Ed. 2d 666, 88 S. Ct. 592 (1967).

Discrediting all of Galella's testimony [note 10] the court found the photographer guilty of harassment, intentional infliction of emotional distress, assault and battery, commercial exploitation of defendant's personality, and invasion of privacy. Fully crediting defendant's testimony, the court found no liability on Galella's claim. Evidence offered by the defense showed that Galella had on occasion intentionally physically touched Mrs. Onassis and her daughter, caused fear of physical contact in his frenzied attempts to get their pictures, followed defendant and her children too closely in an automobile, endangered the safety of the children while they were swimming, water skiing and horseback riding. Galella cannot successfully challenge the court's finding of tortious conduct. [note 11]

Finding that Galella had "insinuated himself into the very fabric of Mrs. Onassis' life . . ." the court framed its relief in part on the need to prevent further invasion of the defendant's privacy. Whether or not this accords with present New York law, there [995] is no doubt that it is sustainable under New York's proscription of harassment. [note 12]

Of course legitimate countervailing social needs may warrant some intrusion despite an individual's reasonable expectation of privacy and freedom from harassment. However the interference allowed may be no greater than that necessary to protect the overriding public interest. Mrs. Onassis was properly found to be a public figure and thus subject to news coverage. See Sidis v. F.R. Publishing Corp., 113 F.2d 806 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 311 U.S. 711, 61 S. Ct. 393, 85 L. Ed. 462 (1940). Nonetheless, Galella's action went far beyond the reasonable bounds of news gathering. When weighed against the de minimis public importance of the daily activities of the defendant, Galella's constant surveillance, his obtrusive and intruding presence, was unwarranted and unreasonable. If there were any doubt in our minds, Galella's inexcusable conduct toward defendant's minor children would resolve it.

Galella does not seriously dispute the court's finding of tortious conduct. Rather, he sets up the First Amendment as a wall of immunity protecting newsmen from any liability for their conduct while gathering news. There is no such scope to the First Amendment right. Crimes and torts committed in news gathering are not protected. See Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 33 L. Ed. 2d 626, 92 S. Ct. 2646 (1972); Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, 403 U.S. 29, 29 L. Ed. 2d 296, 91 S. Ct. 1811 (1971); Dietemann v. Time, Inc., 449 F.2d 245, 249-50 (9th Cir. 1971). See [996] Restatement of Torts 2d § 652(f), comment k (Tent. Draft No. 13, 1967). There is no threat to a free press in requiring its agents to act within the law.

In addition to his substantive claims, Galella challenges the court's (a) refusal to remand the case; (b) refusal to allow a jury trial despite an untimely request; (c) exclusion of Galella from defendant's deposition; (d) failure to recuse himself; (e) consolidation of the temporary injunctive proceedings and trial on the merits. Numerous claims of error in evidentiary rulings are also raised. Little need be said about most of these evidentiary rulings; [note 13] the rulings were either clearly correct or if error, harmless. [note 14] Galella's procedural claims must fail.

Galella's claim against Mrs. Onassis, originally in federal court as an action joined with that against the Secret Service agents, was not automatically stripped of federal pendent jurisdiction by the dismissal of the claim against the agents. United Mineworkers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 86 S. Ct. 1130, 16 L. Ed. 2d 218 (1966); see Almenares v. Wyman, 453 F.2d 1075, 1084 (2d Cir. 1971), cert. denied, 405 U.S. 944, 30 L. Ed. 2d 815, 92 S. Ct. 962 (1972). Whether the claim was to be remanded was within the court's discretion after consideration of judicial economy and fairness to the litigants. United Mineworkers v. Gibbs, supra, 383 U.S. at 726. The motion to remand was made six months after dismissal of the suit against the agents and on the eve of trial; the United States Government had then intervened in the case, [note 15] a series of hearings on the substantive claims had been heard by the federal court, a special master in charge of discovery had been appointed and a number of motions had been heard, and others were pending. [note 16] As no claim of unfairness has been raised, considerations of judicial economy govern and support the court's denial of the motion to remand. A great deal of judicial effort had been expended in covering ground that must be gone over anew had remand been ordered.

Untimely requests for jury trial must be denied unless some cause beyond mere inadvertence is shown. Noonan v. Cunard Steamship Co., 375 [997] F.2d 69 (2d Cir. 1967). Galella explains the delay in making the request as a result of the removal proceedings and the fact that New York does not require a written request for a jury trial. Precisely the same allegations were made and correctly rejected in Leve v. General Motors Corp., 248 F. Supp. 344 (S.D.N.Y. 1965). No error was made in refusing to excuse the untimeliness of the motion; any other decision would have been reversible error. See Noonan, supra, 375 F.2d at 70.

Circumstances of a deposition may be governed by the court's protective order. The court may order that "discovery be conducted with no one present except persons designated by the court." Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c). The extent of the court's authority to determine those present was enlarged by the 1970 revision of the Rules of Discovery. Prior to the revision, Rule 30(b) allowed the court to order discovery to be conducted "with no one present except the parties to the action and the officers and counsel. . . ." In view of the revision, it is clear that the court has the power to exclude even a party, [note 17] although such an exclusion should be ordered rarely indeed.

The grant and nature of protection is singularly within the discretion of the district court and may be reversed only on a clear showing of abuse of discretion. Chemical & Industrial Corp. v. Druffel, 301 F.2d 126, 129 (6th Cir. 1962); Essex Wire Corp. v. Eastern Electric Sales Co., 48 F.R.D. 308, 310 (E.D. Pa. 1969). While we might have assessed the need to exclude Galella differently, we cannot find the court's ruling clearly erroneous. At the time the order was issued, Galella had already been charged with violation of the court's temporary restraining order which was entered to protect the defendant from further harassment. Such conduct could be deemed to reflect both an irrepressible intent to continue plaintiff's harassment of defendant and his complete disregard for judicial process. Anticipation of misconduct during the examination could reasonably have been founded on either.

The court's refusal to recuse himself was correct. See United States ex rel. Brown v. Smith, 200 F. Supp. 885, 930 (D. Vt. 1961), rev'd on other grounds, 306 F.2d 596 (2d Cir. 1962), cert. denied, 372 U.S. 959, 10 L. Ed. 2d 11, 83 S. Ct. 1012 (1963); United States v. Sclafani and Ross, 487 F.2d 245, 255 (2d Cir. 1973). A judge may be disqualified for bias only on motion supported by a written affidavit of facts supporting the claim of bias and a certificate of good faith from the counsel of record. 28 U.S.C. § 144. Galella failed to comply with the statute; no showing was made of a legal basis for the claim, no motion was made nor affidavit filed. Informal requests to the court, or failure to comply with the statute because of an expectation of denial, however well founded, cannot be substituted for compliance with § 144.

Galella claims that notice given him of consolidation under Rule 65(a)(2) of preliminary injunction proceedings and the trial was inadequate in that he was not advised of the consolidation sufficiently in advance of trial to properly prepare. The claim borders on the frivolous. The required notice under Rule 65 is solely for the purpose of alerting the parties that the hearing is to be the final determination of the action. See 7 J. Moore, Federal Practice para. 65.04[4]. Galella knew five weeks before trial that the actions on the preliminary and permanent injunction had been consolidated. There is thus no merit to an attack on sufficiency of notice under Rule 65.

Essentially Galella's challenge is one of denial of due process; he contends [998] that the court's scheduling of trial unfairly limited his preparation for trial. The claim is based generally on depositions and discovery either not made or not completed. [note 18] Here any lack of discovery was due to plaintiff's own dilatory actions; it was not error for the court to proceed. See Eli Lilly & Co. v. Generix Drug Sales, 460 F.2d 1096, 1105 (5th Cir. 1972). Issue was joined and counterclaim filed by September, 1970, and the case removed in October, 1970. Yet even by the time of trial in 1972 Galella had not yet noticed for deposition defendant's husband (a witness Galella says he was deprived of deposing by the scheduling.) [note 19]

Scheduling of trials is for the trial courts. Only where actual and substantial prejudice can be shown will a court's calendar orders be reviewed. Galella has made no such showing. He himself requested consolidation in October, 1971; that motion was withdrawn in January, 1972; the court however indicated that it would consolidate the proceedings as both the plaintiff and defendant had requested, and planned to go to trial as soon as a space opened on his calendar. Galella had five weeks' notice of the expected date of trial.

Injunctive relief is appropriate. Galella has stated his intention to continue his coverage of defendant so long as she is newsworthy, and his continued harassment even while the temporary restraining orders were in effect indicate that no voluntary change in his technique can be expected. New York courts have found similar conduct sufficient to support a claim for injunctive relief. Flamm v. Van Nierop, 56 Misc.2d 1059, 291 N.Y.S.2d 189 (1968). [note 20]

The injunction, however, is broader than is required to protect the defendant. Relief must be tailored to protect Mrs. Onassis from the "paparazzo" attack which distinguishes Galella's behavior from that of other photographers; it should not unnecessarily infringe on reasonable efforts to "cover" defendant. Therefore, we modify the court's order to prohibit only (1) any approach within twenty-five (25) feet of defendant or any touching of the person of the defendant Jacqueline Onassis; (2) any blocking of her movement in public places and thoroughfares; (3) any act foreseeably or reasonably calculated to place the life and safety of defendant in jeopardy; and (4) any conduct which would reasonably be foreseen to harass, alarm or frighten the defendant.

Any further restriction on Galella's taking and selling pictures of defendant for news coverage is, however, improper and unwarranted by the evidence. See Estate of Hemingway v. Random House, Inc., 49 Misc.2d 726, 268 N.Y.S.2d 531, 535, aff'd 25 App. Div. 2d 719, 269 N.Y.S.2d 366 (1966); Youssoupoff v. Columbia Broadcasting, 41 Misc.2d 42, 244 N.Y.S.2d 701, 704, aff'd 19 App. Div. 2d 865, 244 N.Y.S.2d 1 (1963); Thompson v. C.P. Putnam's Sons, 40 Misc.2d 608, [999] 243 N.Y.S.2d 652, 654 (1965).

Likewise, we affirm the grant of injunctive relief to the government modified to prohibit any action interfering with Secret Service agents' protective duties. Galella thus may be enjoined from (a) entering the children's schools or play areas; (b) engaging in action calculated or reasonably foreseen to place the children's safety or well being in jeopardy, or which would threaten or create physical injury; (c) taking any action which could reasonably be foreseen to harass, alarm, or frighten the children; and (d) from approaching within thirty (30) feet of the children.

Taxation of costs of a daily transcript of trial may be assessed against a party by the court, where they are "necessarily obtained for use in the case." 28 U.S.C. § 1920. See Oscar Gruss & Son v. Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co., 422 F.2d 1278 (2d Cir. 1970). Galella was ordered to pay the cost of four daily copies, one each for the government intervenor and the court, and two for defendant. [note 21] To assess the losing party with the premium cost of daily transcripts, necessity--beyond the mere convenience of counsel--must be shown. Delaware Valley Marine Supply Co. v. American Tobacco Co., 199 F. Supp. 560, 561 (E.D. Pa. 1960). We cannot say that no such showing has been made here. [note 22] There does not, however, appear any justification for allowing multiple copies to the defendant. Galella therefore should not be taxed for any more than the cost of a transcript at the daily rate for three copies, one for the defendants, one for the intervenor and one for the court. [note 23] See Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co., 379 U.S. 227, 235, 13 L. Ed. 2d 248, 85 S. Ct. 411 (1964):

"We do not read that Rule [Rule 54(d)] as giving district judges unrestrained discretion to tax costs to reimburse a winning litigant for every expense he has seen fit to incur in the conduct of his case. Items proposed by winning parties as costs should always be given careful scrutiny. Any other practice would be too great a movement in the direction of some systems of jurisprudence that are willing, if not indeed anxious, to allow litigation costs so high as to discourage litigants from bringing lawsuits, no matter how meritorious they might in good faith believe their claims to be."

As modified, the relief granted fully allows Galella the opportunity to photograph and report on Mrs. Onassis' public activities. Any prior restraint on news gathering is miniscule and fully supported by the findings.

Affirmed in part, reversed in part and remanded for modification of the judgment in accordance with this opinion. Costs on appeal to be taxed in favor of appellees.

TIMBERS, Circuit Judge (concurring in part and dissenting in part):

With one exception, I concur in the judgment of the Court and in the able majority opinion of Judge Smith.

With the utmost deference to and respect for my colleagues, however, I am constrained to dissent from the judgment of the Court and the majority opinion to the extent that they modify the injunctive relief found necessary by the district court to protect Jacqueline Onassis [1000] and her children, Caroline B. and John F. Kennedy, Jr., from the continued predatory conduct of the self-proclaimed paparazzo Galella.

We start with what I take to be common ground that "a district court has broad discretion to enjoin possible future violations of law where past violations have been shown"; that "the court's determination [that permanent injunctive relief is required] should not be disturbed on appeal unless there has been a clear abuse of discretion"; and that "the party seeking to overturn the district court's exercise of discretion has the burden of showing that the court abused that discretion, and the burden necessarily is a heavy one." SEC v. Manor Nursing Centers, Inc., 458 F.2d 1082, 1100 (2 Cir. 1972). That certainly is the settled law in this Circuit. And it is the command of Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a).

In the instant case, after a six week trial at which 25 witnesses testified, hundreds of exhibits were received and a 4,714 page record was compiled, Judge Cooper filed a careful, comprehensive 40 page opinion, 353 F. Supp. 184, which meticulously sets forth detailed findings of fact and conclusions of law. As for the provisions of the injunction requiring Galella to keep certain distances away from Mrs. Onassis and her children (from the modification of which I dissent), Judge Cooper stated his reasons for these provisions as follows:

"For practical reasons, the injunction cannot be couched in terms of prohibitions upon Galella's leaping, blocking, taunting, grunting, hiding and the like. Nor have abstract concepts--harassing, endangering--proved workable. No effective relief seems possible without the fixing of proscribed distances.

We must moreover make certain plaintiff keeps sufficiently far enough away to avoid problems as to compliance with the injunction and injurious disobedience. Disputes concerning his compliance may be frequent, thereby necessitating repeated application to the Court. Hence, the restraint must be clear, simple and effective so that Galella's substantial compliance cannot seriously be disputed unless a violation occurs.

Of major importance in determining the scope of the relief to be afforded here is the attitude which Galella has demonstrated toward the process of this Court in the past. Galella blatantly violated our restraining orders of October 8 and December 2, 1971. He did so deliberately and in full knowledge of the fact of his violation. His deliberate disobedience to the subpoena and his attempts to obstruct justice with respect to Exhibit G, together with the perjury that infected his testimony, do not warrant mere token relief.

In light of Galella's repeated misbehavior, it is clear that only a strong restraint--an injunction which will clearly protect Mrs. Onassis' rights and leave no room for quibbling about compliance and no room for evasion or circumvention--is appropriate in this case.

* * *

As for the actual distance to be proscribed, we must bear in mind that plaintiff never moved to modify the distances heretofore imposed by our restraining order, even after the Court had clearly and explicitly invited him to do so if he could prove it was too harsh. (Minutes, Proceedings January 19, 1972, p. 31)." 353 F. Supp. at 237.

I have set forth the foregoing explanation by Judge Cooper of his reasons for the critical distance provisions of the injunction because they are weighty findings by the trial judge who had the benefit of seeing the parties before him and who obviously was in a better position than we to judge their demeanor. I feel very strongly that such findings should not be set aside or drastically modified by our Court unless [1001] they are clearly erroneous; and I do not understand the majority to suggest that they are.

But here is what the majority's modification of the critical distance provisions of the injunction has done:

DISTANCES GALELLA IS REQUIRED TO MAINTAINAS PROVIDED IN DISTRICT COURT INJUNCTION AS MODIFIED BY COURT OF APPEALS MAJORITY

From home of Mrs. Onassis and her children 100 yards - No restriction

From children's schools 100 yards - Restricted only from entering schools or play areas*

From Mrs. Onassis personally 50 yards - 25 feet and not to touch her

From children personally 75 yards - 30 feet*

In addition to modifying the distance restrictions of the injunction, the majority also has directed that Galella be prohibited from blocking Mrs. Onassis' movement in public places and thoroughfares; from any act "foreseeably or reasonably calculated" to place Mrs. Onassis' life and safety in jeopardy (and similarly with respect to her children); and from any conduct which would "reasonably be foreseen" to harass, alarm or frighten Mrs. Onassis (and similarly with respect to her children).

With deference, I believe the majority's modification of the injunction in the respects indicated above to be unwarranted and unworkable. Briefly summarized, the following are the reasons for my dissent from the modification of the injunction:

(1) The majority ignores the weighty findings of the district court. Without holding them clearly erroneous, Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a), the majority simply sets them aside and substitutes its own perimeters for those carefully and wisely drawn by the district court.

(2) This results, for example, in a wholly unexplained and anomalous 84% reduction of the distance Galella is required to keep away from Mrs. Onassis (from 50 yards to 25 feet), and an equally implausible 87% reduction of the distance he is required to keep away from the children (from 75 yards to 30 feet).

(3) It further results in no restriction whatsoever against Galella's hovering at the entrance to the home of Mrs. Onassis and her children (where he has caused such agonizing humiliation in the past), or at the schools attended by the children--just so he does not physically [1002] enter their schools or play areas. This strikes me as an invitation for trouble.

(4) The majority, in substituting its own injunctive provisions for those of the district court, has couched its prohibitions in terms of conduct "foreseeably or reasonably calculated" to endanger the life or safety of Mrs. Onassis or her children, or conduct which would "reasonably be foreseen" to harass, alarm or frighten them. (emphasis added). These are just the sort of abstract concepts which the district court found to be unworkable and ineffective. 353 F. Supp. at 237. They do not comply with the specificity requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d) ("Every order granting an injunction . . . shall be specific in terms. . . ."). This has been construed by our Court to require that "the party enjoined must be able to ascertain from the four corners of the order precisely what acts are forbidden." Sanders v. Air Line Pilots Association, 473 F.2d 244, 247 (2 Cir. 1972). See International Longshoremen's Association v. Philadelphia Marine Trade Association, 389 U.S. 64, 76, 19 L. Ed. 2d 236, 88 S. Ct. 201 (1967); Brumby Metals, Inc. v. Bargen, 275 F.2d 46, 49 (7 Cir. 1960). The district court was justifiably concerned--in view of Galella's record of outrageous disregard of the court's previous restraining orders--that it would be confronted with repeated compliance applications in the future. The majority's substitution of such abstract concepts as "reasonably foreseen" and "foreseeably calculated" for the clear, simple and effective distance restrictions in the district court injunction seems to me virtually to assure the compliance disputes that the district court wisely sought to avert.

(5) In modifying the injunctive relief granted by the district court, I fear that the majority has overlooked the fact that the record shows that Galella in the past has jeopardized the lives and safety of Mrs. Onassis and her children and has done so in the teeth of previous restraining orders of the district court. One of the particularly weighty findings of the district court in support of the scope of injunctive relief granted was that "Galella blatantly violated our restraining orders of October 8 and December 2, 1971. He did so deliberately and in full knowledge of the fact of his violation." 353 F. Supp. at 237. Our Court has been particularly adamant against disturbing a district court's grant of injunctive relief when the parties enjoined "continued to violate the . . . laws even after a consent decree had been entered enjoining them from such conduct" and when "they have persisted in their contention that their past conduct was not improper . . . ." SEC v. Koenig, 469 F.2d 198, 202 (2 Cir. 1972), citing SEC v. MacElvain, 417 F.2d 1134, 1137 (5 Cir. 1969), cert. denied, 397 U.S. 972, 25 L. Ed. 2d 265, 90 S. Ct. 1087 (1970), and SEC v. Manor Nursing Centers, Inc., supra.

(6) All else aside, the wisdom and fairness of the distance restrictions which the district court provided for in its permanent injunction--which are substantially identical to those in its temporary restraining order of December 2, 1971 and which were in effect until July 20, 1972--appear to be borne out by the failure of Galella ever to request the district court to modify such restrictions, despite the express invitation of the district court to Galella to do so: "As for the actual distance to be proscribed, we must bear in mind that plaintiff never moved to modify the distances heretofore imposed by our restraining order, even after the Court had clearly and explicitly invited him to do so if he could prove it was too harsh." 353 F. Supp. at 237. Pursuant to the district court's decision of July 5, 1972 [1003] requesting that the form of injunction be settled on three days notice, both sides submitted proposed judgments which were identical in all respects here material; neither in his proposed form of judgment nor in his memorandum accompanying it did Galella interpose any objection whatsoever to the distance restrictions on the ground that they were too harsh or onerous. Since the district court never was afforded an opportunity to pass upon such questions which are raised for the first time on appeal, I see no compelling reason for departing from the long settled rule in this Circuit that such matters should not be reached by us on appeal. Ring v. Authors' League of America, 186 F.2d 637, 641 (2 Cir.) (L. Hand, C.J.: "If a party's sensibilities are so tender, the least we must demand is that he make known his complaint at a time when it can be remedied."), cert. denied sub nom. Ring v. Spina, 341 U.S. 935, 95 L. Ed. 1363, 71 S. Ct. 854 (1951); United States v. Five Cases, 179 F.2d 519, 523-24 (2 Cir.) (Swan, C.J., aff'g judgment entered on jury verdict after trial before Hincks, D.J.), cert. denied, 339 U.S. 963, 94 L. Ed. 1372, 70 S. Ct. 997 (1950). At the very least, if there is to be any modification of the injunction with respect to the distance provisions (and I believe none is warranted), then the case should be remanded to the district court which obviously is in a far better position to make such determinations after a hearing than are we. After all, what possible basis is there in this record for us as appellate judges to say that Galella should keep 25 feet, rather than 50 yards, away from Mrs. Onassis; or that he should remain 30 feet, rather than 75 yards, away from the children?

(7) Finally, I am utterly unable to find any basis in the record or any justification as a matter of law for the majority's modification of the injunction so as to limit the protection provided for the children to the "grant of injunctive relief to the government modified to prohibit any action interfering with Secret Service agents' protective duties." (emphasis added). Supra 487 F.2d at 999. Just two paragraphs before this, the majority has modified the injunction to prohibit Galella from engaging in four types of conduct directed at "defendant Jacqueline Onassis", with no mention of the children. Id. And yet the claim for injunctive relief sought in the counterclaim filed March 8, 1971 was explicitly "for the personal safety of defendant [Mrs. Onassis] and of her infant children". The judgment entered July 20, 1972 provided, in paragraph 4, for injunctive relief for the protection of Mrs. Onassis and both of her children; the only reference to the government in the injunctive provisions of the judgment is in subparagraph (viii) of paragraph 4 where Galella is enjoined from "otherwise interfering with any agent of the United States of America in the performance of protective duties relating to Caroline B. Kennedy or John F. Kennedy, Jr." As I read the majority's modification of the injunction, to the extent that it distinguishes between protection for Mrs. Onassis and that for the children, limiting the latter to the grant of injunctive relief to the government, the net effect is to strip the children of any protection under the injunction after they reach age 16 when their protection by the Secret Service ceases. 18 U.S.C. § 3056 (1970). For Caroline, who was born November 27, 1957, this means that one of her birthday presents--less than two months away--will be exposure to the resumed predatory conduct of the paparazzo Galella who will be totally unrestrained with respect to her by the injunction as modified by the majority. For John, who was born November 25, 1960, he has only three [1004] years to wait for similar exposure. To strip these children, before they reach their majority, of the protection of the injunction of the United States District Court below, is to deny to them and to their mother the very least to which they are entitled under the law. I most respectfully dissent.

Source: bc.edu

Dior Suit

Jackie's Suit Against Christian Dior

122 Misc.2d 603 (1984)

Jacqueline K. Onassis, Plaintiff, v. Christian Dior — New York, Inc., et al., Defendants.

Supreme Court, Special Term, New York County.

January 11, 1984

Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy for plaintiff. Windels, Marx, Davies & Ives for Christian Dior — New York, Inc., defendant. Breed, Abbott & Morgan for Lansdowne Advertising, Inc., defendant. Proskauer, Rose, Goetz & Mendelsohn for Richard Avedon, defendant. Lowen & Abut (Charles C. Abut of counsel), for Ron Smith Celebrity Look-Alikes, defendant.

EDWARD J. GREENFIELD, J.

This case poses for judicial resolution the question of whether the use for commercial purposes of a "lookalike" of a well-known personality violates the right of privacy legislatively granted by enactment of sections 50 and 51 of the Civil Rights Law. Put another way, can one person enjoin the use of someone else's face? The questions appear not to have been definitively answered before.

Plaintiff, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, former First Lady of the United States, widow of President John F. Kennedy, one of the world's most powerful men, and of Aristotle Onassis, one of the world's wealthiest men, but a well-known personality in her own right, moves for a preliminary injunction under the Civil Rights Law to restrain defendants, all of whom were associated with an advertising campaign to promote the products and the image of Christian Dior — New York, Inc., from using or distributing a certain advertisement, and for associated relief. She alleges simply in her complaint that defendants have knowingly caused the preparation and publication of an advertisement for Dior products which includes her likeness in the form of a photograph of lookalike Barbara Reynolds; that Reynolds' picture causes her to be identified with the ad to which she has not given her consent; that this was a violation of her rights of privacy and that it caused her irreparable injury.

Defendant, Christian Dior — New York, Inc., is the corporate entity which controls advertising and publicity for the 35 United States licensees who sell varied lines of merchandise under the coveted Dior label. The use of a well-known designer name in marketing goods is to render the product distinctive and desirable, to impart to the product a certain cachet, and to create in the public a mindset or over-all impression so that the designer names are readily associated and become synonymous with a certain status and class of qualities.

So it was that J. Walter Thompson's Lansdowne Division, in conjunction with noted photographer Richard Avedon, hit upon the idea of a running series of ads featuring a trio known as the Diors (one female and two males), who were characterized by an article in Newsweek magazine as idle rich, suggestively decadent, and aggressively chic. Indeed, it was suggested that this menage a trois, putatively inspired by the characters portrayed by Noel Coward, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in Coward's 1933 play "Design for Living", would become the most notorious personae in advertising since Brooke Shields refused to let anything come between her and her Calvins (for the uninitiated, blue jeans advertised under designer Calvin Klein's label). To emphasize the impression of the unconventional, the copy for one ad had read, "When the Diors got away from it all, they brought with them nothing except `The Decline of the West' and one toothbrush." Evidently, to stir comment, the relationship portrayed in the ad campaign was meant to be ambiguous, "to specify nothing but suggest everything." The 16 sequential ads would depict this steadfast trio in varying situations leading to the marriage of two (but not the exclusion of the third), birth of a baby, and their ascent to Heaven (subject to resurrection on demand).

Thus, the Diors, and by association their products, would be perceived as chic, sophisticated, elite, unconventional, quirky, audacious, elegant, and unorthodox. The advertisement for the wedding, which is the one challenged here, is headed "Christian Dior: Sportswear for Women and Clothing for Men." Portrayed in the ad are the happy Dior trio attended by their ostensible intimates, all ecstatically beaming — Gene Shalit, the television personality, model Shari Belafonte, actress Ruth Gordon, and Barbara Reynolds, a secretary who bears a remarkable resemblance to plaintiff Jacqueline Onassis. The copy, in keeping with the desired attitude of good taste and unconventionality, reads: "The wedding of the Diors was everything a wedding should be: no tears, no rice, no in-laws, no smarmy toasts, for once no Mendelssohn. Just a legendary private affair." Of course, what stamps it as "legendary" is the presence of this eclectic group, a frothy mix, the most legendary of which would clearly be Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, shown discreetly behind Gordon and Shalit, obviously delighted to be in attendance at this "event".

That the person behind Gordon and Shalit bore a striking resemblance to the plaintiff was no mere happenstance. Defendants knew there was little or no likelihood that Mrs. Onassis would ever consent to be depicted in this kind of advertising campaign for Dior. She has asserted in her affidavit, and it is well known, that she has never permitted her name or picture to be used in connection with the promotion of commercial products. Her name has been used sparingly only in connection with certain public services, civic, art and educational projects which she has supported. Accordingly, Lansdowne and Avedon, once the content of the picture and the makeup of the wedding party had been determined, contacted defendant Ron Smith Celebrity Look-Alikes to provide someone who could pass for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. That agency, which specializes in locating and providing persons who bear a close resemblance to well-known personalities on request (and for a fee), came up with defendant Barbara Reynolds, regularly an appointments secretary to a Congressman, who, with appropriate coiffure and appointments, looks remarkably like Mrs. Onassis, and has made this resemblance an adjunct to her career.

The ad was run in September and October of 1983 in several upscale publications including Esquire, Harper's Bazaar, the New Yorker, and the New York Times Magazine. It received widespread circulation, and apparently was the subject of considerable comment, as was the entire series. Dior reportedly committed $2.5 million to the campaign, and boasted that as a result, sales went through the roof. In opposition to the application for an injunction, defendants urge, among other things, that it is unnecessary because the ad has already appeared, and it is not scheduled for republication. However, they declined to enter into any formal stipulation to that effect, and trade papers are abuzz with speculation about the resurrection and reincarnation of the campaign, with possible television showings to reach an even wider audience. Moreover, the case presents an important question under the privacy law, and it is appropriate that it be judicially resolved. (Matter of Baumann & Son Buses v Board of Educ., 46 N.Y.2d 1061, 1063; Le Drugstore Etats Unis v New York State Bd. of Pharmacy, 33 N.Y.2d 298, 301.)

Section 50 of the New York Civil Rights Law provides: "A person, firm or corporation that uses for advertising purposes, or for the purposes of trade, the name, portrait or picture of any living person without having first obtained the written consent of such person * * * is guilty of a misdemeanor."

Having defined the offense, and declaring it to be criminal, section 51 of the Civil Rights Law goes on to provide civil remedies for violation as well, including injunction and damages. "Any person whose name, portrait or picture is used within this state for advertising purposes or for the purposes of trade without the written consent first obtained as above provided may maintain an equitable action in the supreme court of this state against the person, firm or corporation so using his name, portrait or picture, to prevent and restrain the use thereof; and may also sue and recover damages for any injuries sustained by reason of such use and if the defendant shall have knowingly used such person's name, portrait or picture in such manner as is forbidden or declared to be unlawful by section fifty of this article, the jury, in its discretion, may award exemplary damages".

Once the violation is established, the plaintiff may have an absolute right to injunction, regardless of the relative damage to the parties. (Blumenthal v Picture Classics, 235 App Div 570, affd 261 N.Y. 504; Loftus v Greenwich Lithographing Co., 192 App Div 251; Durgom v Columbia Broadcasting Systems, 29 Misc.2d 394, 395.)

Is there a violation? Defendants, urging a strict and literal compliance with the statute, say that there is not. Plaintiff, arguing for a broader interpretation, insists that there is. As a general proposition, sections 50 and 51 of the Civil Rights Law, which created a new statutory right, being in derogation of common law, receive a strict, if not necessarily a literal construction. (Shields v Gross, 58 N.Y.2d 338, 345; Arrington v New York Times Co., 55 N.Y.2d 433, 439.) However, "`[s]ince its purpose "is remedial * * * to grant recognition to the newly expounded right of an individual to be immune from commercial exploitation" (Flores v Mosler Safe Co., 7 N.Y.2d 276, 280-281; see Lahiri v Daily Mirror, 162 Misc. 776, 779), section 51 of the Civil Rights Law has been liberally construed over the ensuing years.'" (Stephano v News Group Pub., 98 A.D.2d 287, 295.)

Plaintiff's name appears nowhere in the advertisement. Nevertheless, the picture of a well-known personality, used in an ad and instantly recognizable, will still serve as a badge of approval for that commercial product. It is designed to "catch the eye and focus it on the advertisement". (Negri v Schering Corp., 333 F.Supp. 101, 105.) That is why the use of a person's "portrait or picture" without consent is also proscribed. Just what is comprehended by the term "portrait or picture"?

In Negri v Schering Corp. (supra), plaintiff, the well-known movie actress of the 1920's, Pola Negri, objected to the publication of an advertisement in 1969 showing a scene from one of her early movies with words issuing from her mouth in the balloon caption suggesting the use of the antihistamine drug Polaramine. To defendant's contention that the picture did not really show plaintiff as she was then, the Southern District Court, applying New York law, held (p 105) that as long as the ad portrayed a recognizable likeness, it was actionable, declaring, "If a picture so used is a clear and identifiable likeness of a living person, he or she is entitled to recover damages suffered by reason of such use".

In Ali v Playgirl, Inc. (447 F.Supp. 723), the portrait or picture was not an actual photo, but a composite photodrawing depicting a naked black man in a boxing ring, with the recognizable facial features of the former world's heavyweight champion. The Southern District Court, again applying New York law, held that the phrase "portrait or picture" as used in section 51 of the Civil Rights Law is not restricted to actual photographs, but comprises any representations which are recognizable as likenesses of the complaining individual. In that case, the picture represented something short of actuality — somewhere between representational art and a cartoon.

In Loftus v Greenwich Lithographing Co. (192 App Div 251, supra), the objection again was not to an actual picture of the plaintiff, but to an advertising poster for a movie called "Shame" which showed a sketch of a female figure in a costume plaintiff had popularized in a Ziegfeld production. The court rejected defendant's contention that the poster was not an actual depiction of plaintiff. Despite changes that were made as between plaintiff's actual picture and defendant's drawing, the court found it evident that the drawing took plaintiff's appearance as its starting point, and declared that slight changes or deviations would not thwart the application of the wholesome provisions of the Civil Rights Law.